Women’s History czyli technologia reprodukcji

In the Matter of Baby M: 1988 Plaintiffs: William and Elizabeth Stern

|

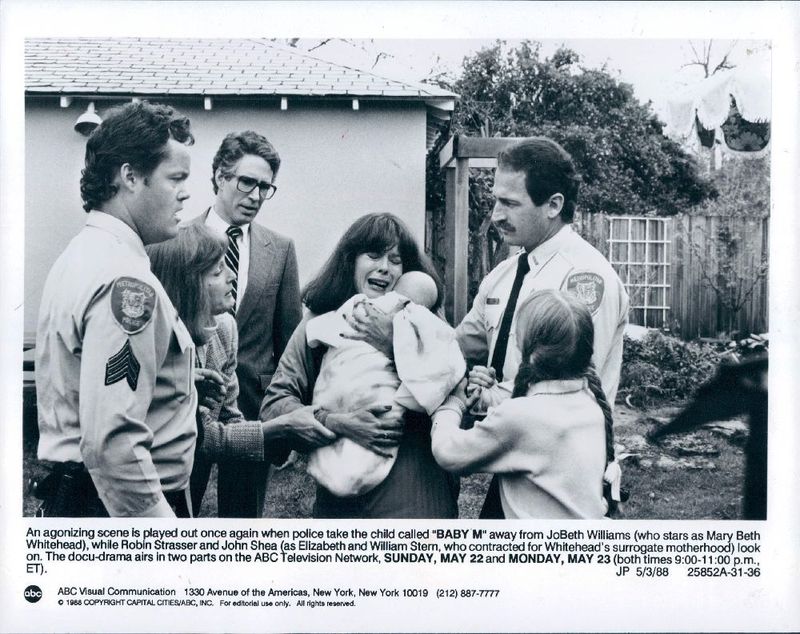

http://www.gale.cengage.com/free_resources/whm/trials/babym.htm Defendant: Mary Beth Whitehead Chief Lawyers for Defendant: Harold Cassidy and Randy Wolf Chief Lawyers for Plaintiffs: Frank Donahue and Gary Skoloff Plaintiffs’ Claim: That Mary Beth Whitehead should surrender the child she conceived via artificial insemination with William Stern’s sperm, in compliance with the terms of a “Surrogate Parenting Agreement” made between Whitehead and Stern prior to the child’s conception Justices: Robert Clifford, Marie L. Garibaldi, Alan B. Handler, Daniel O’Horn, Stewart G. Pollock, Gary S. Stein, and Chief Justice Robert N. Wilentz Place: Trenton, New Jersey Date of Decision: February 3, 1988 Verdict: Mary Beth Whitehead’s parental rights were terminated and Elizabeth Stern was granted the right to immediately adopt William Stern’s and Whitehead’s daughter. The New Jersey Supreme Court overturned this verdict in part on February 2, 1988, when it restored Whitehead’s parental rights and invalidated Elizabeth Stern’s adoption, but granted William Stern custody of the infant. Significance: This was the first widely followed trial to wrestle with the ethical questions raised by “reproductive technology.” Melissa Stern’s conception took place under an agreement signed at Noel Keane’s Infertility Center of New York on February 5, 1985. There were three parties to the agreement: Richard Whitehead gave his consent to the contract’s “purposes, intents, and provisions” and to the insemination of Mary Beth Whitehead, his wife, with the sperm of William Stern. In addition, since any child born to Mary Beth Whitehead would legally be the child of her husband, he agreed that he would “surrender immediate custody of the child” and “terminate his parental rights.” Mary Beth Whitehead agreed to be artificially inseminated and to form no “parent-child relationship” with the baby. She agreed that she would, upon delivery of the child, surrender her parental rights to William Stern; and she acknowledged that she would, during the term of the pregnancy, relinquish her right to make a decision about an abortion. She was permitted to seek an abortion only if the fetus was “physiologically abnormal” or if the inseminating physician agreed an abortion was required to insure her “physical health.” Whitehead then agreed that it was William Stern’s right to require amniocentesis testing and that she would “abort the fetus upon demand of William Stern should a congenital or genetic abnormality be diagnosed.” Despite the limitation of Whitehead’s right to seek an abortion, the contract allocated to Stern responsibility for the child in the event that Whitehead refused to fulfill this part of her agreement: “If Mary Beth Whitehead refuses to abort the fetus upon demand of William Stern, his obligations as stated in this Agreement shall cease forthwith, except as to obligations of paternity imposed by statute.” Finally, the Whiteheads “agree[d] to assume all risks, including the risk of death, which are incidental to conception, pregnancy, [and] childbirth.” Stern agreed to pay $10,000 to Whitehead. Although the $10,000 was described as “compensation for services and expenses” and the contract specifically states that the fee should “in no way be construed as a fee for termination of parental rights or a payment in exchange for a consent to surrender the child for adoption,” it was payable only upon surrender of a live infant. If Whitehead suffered a miscarriage prior to the fifth month of pregnancy, she would receive no compensation; if the “child is miscarried, dies or is stillborn subsequent to the fourth month of pregnancy and said child does not survive,” Stern agreed to pay Whitehead $1,000. He also paid $10,000 to Noel Keane, for his services in arranging the surrogacy agreement. Stern’s wife, Elizabeth, was not a party to the agreement, nor was she mentioned by name. The contract referred to her only as Stern’s wife. The first such reference is the statement that the contract’s “sole purpose . . . is to enable William Stern and his infertile wife to have a child which is biologically related to William Stern.”‘ The other reference states, “In the event of the death of William Stern, prior or subsequent to the birth of said child, it is hereby understood and agreed by Mary Beth Whitehead, Surrogate, and Richard Whitehead, her husband, that the child will be placed in the custody of William Stern’s wife.” Events did not go according to the contractual script. On March 27, 1986, Whitehead gave birth to a daughter. She named the infant “Sara Elizabeth Whitehead,” took her home, and turned down the $10,000. On Easter Sunday, March 30, the Sterns took the infant to their home. The baby was back at the Whitehead home on March 31; in the second week of April, Whitehead told the Sterns she would never be able to give up her daughter. The Sterns responded by hiring attorney Gary Skoloff to fight for the contract’s enforcement. The police arrived to remove “Melissa Elizabeth Stern” from the Whitehead’s custody; shown the birth certificate for “Sara Elizabeth Whitehead,” they left. When the police returned, Whitehead passed her daughter through an open window to her husband and pleaded with him to make a run for it. The Trial Begins The trial commenced on January 5, 1987, by which time a representative had been appointed for the child, known as “Baby M,” which stood for Melissa. The Sterns had received temporary custody. Whitehead, who had been ordered by Judge Harvey Sorkow to discontinue breast-feeding the child, had been temporarily awarded two one-hour visits each week, “strictly supervised under constant surveillance . . . in a sequestered, supervised setting to prevent flight or harm.” Skoloff framed the “issue to be decided” as “whether a promise to make the gift of life should be enforced.” He stated that “Mary Beth Whitehead agreed to give Bill Stern a child of his own flesh and blood” and emphasized that Elizabeth Stern’s multiple sclerosis “rendered her, as a practical matter, infertile . . . because she could not carry a baby without significant risk to her health.” Harold Cassidy, the attorney for Whitehead, offered an alternative view in his own opening remarks: “The only reason that the Sterns did not attempt to conceive a child was . . . because Mrs. Stern had a career that had to be advanced. . . . What Mrs. Stern has is [multiple sclerosis] diagnosed as the mildest form. She was never even diagnosed until after we deposed her in this case. . . . We’re here,” Cassidy summed up, “not because Betsy Stern is infertile but because one woman stood up and said there are some things that money can’t buy.” A neurologist affiliated with the Mount Sinai School of Medicine testified that Elizabeth Stern was afflicted with “a very, very, very slight case of MS, if any.” When the issue of custody was brought up, Skoloff stated that contract law and the infant’s best interests dictated that exclusive custody should be awarded to the Sterns: “If there is one case in the United States, where joint custody will not work, where visitation rights will not work, where maintaining parental rights will not work, this is it.” He addressed Sorkow directly: “Your Honor, under both the contract theory and the best-interest theory, you must terminate the rights of Mary Beth Whitehead and allow Bill Stern and Betsy Stern to be Melissa’s mother and father.” Baby M.’s representative, Lorraine Abraham, took the stand to make her own recommendation. She told the court that she had relied, in part, upon the opinions of three experts in forming her own conclusion: psychologist Dr. David Brodzinsky; social worker Dr. Judith Brown Greif; and psychiatrist Dr. Marshall Schechter. Abraham stated that the experts “will . . . recommend to this court that custody be awarded to the Sterns and visitation denied at this time.” Abraham, required to offer her own opinion as Baby M’s representative, added that she was “compelled by the overwhelming weight of [the three experts’] investigation to join in their recommendation.” During Elizabeth Stern’s testimony, she was asked by Randy Wolf, one of Whitehead’s lawyers, “Were you concerned about what effect taking the baby away from Mary Beth Whitehead would have on the baby?” Stern responded: “I knew it would be hard on Mary Beth and in Melissa’s best interest.” Wolf then said: “Now, I believe you testified that if Mary Beth Whitehead receives custody of the baby, you don’t want to visit.” Stern replied, “That is correct. I do not want to visit.” Skoloff next raised questions about Whitehead’s fitness as a mother. Whitehead had hidden in Florida with Baby M shortly after the infant’s birth, and Skoloff represented this as evidence of instability. He then played for the court a taped telephone conversation between Mary Beth Whitehead and William Stern: Stern: I want my daughter back. Whitehead: And I want her, too, so what do we do, cut her in half? Stern: No, no, we don’t cut her in half. Whitehead: You want me, you want me to kill myself and the baby? Stern: No, that’s why I gave her to you in the first place, because I didn’t want you to kill yourself. Whitehead: I’ve been breast-feeding her for four months. She’s bonded to me, Bill. I sleep in the same bed with her. She won’t even sleep by herself. What are you going to do when you get this kid that’s screaming and carrying on for her mother? Stern: I’ll be her father. I’ll be a father to her. I am her father. Stern: You made an agreement. You signed an agreement. Whitehead: Forget it, Bill. I’ll tell you right now I’d rather see me and her dead before you get her. The following day, it was Mary Beth Whitehead’s turn to testify. One of her attorneys asked, “If you don’t get custody of Sara, do you want to see her?” Whitehead replied: Yes, I’m her mother, and whether this court only lets me see her two minutes a week, two hours a week, or two days, I’m her mother and I want to see her, no matter what. Expert testimony followed. Dr. Lee Salk, the influential child psychologist, testified for the Sterns. Already termed a “third-party gestator” in court documents, Whitehead would now be called “a surrogate uterus.” “The legal term that’s been used is ‘termination of parental rights,'” Salk began, and I don’t see that there were any “parental rights” that existed in the first place. . . . The agreement involved the provision of an ovum by Mrs. Whitehead for artificial insemination in exchange for $10,000 . . . and so my feeling is that in both structural and functional terms, Mr. and Mrs. Stern’s role as parents was achieved by a surrogate uterus and not a surrogate mother. Dr. Marshall Schechter testified, as predicted by Abraham, that he believed custody should be awarded to the Sterns. He declared that Whitehead suffered from a “borderline personality disorder” and that “handing the baby out of the window to Mr. Whitehead is an unpredictable, impulsive act that falls under this category.” Then, citing (among other things) that Whitehead dyed her hair to conceal its premature whiteness, he added the diagnosis of “narcissistic personality disorder.” Boston psychiatric social worker Dr. Phyllis Silverman refuted Schechter’s characterization of Whitehead’s behavior as “crazy”: Mrs. Whitehead’s reaction is like that of other “birth mothers” who suffer pain, grief, and rage for as long as 30 years after giving up a child. The bond of a nursing mother with her child is very powerful. “By These Standards, We Are All Unfit Mothers” Outside the courtroom, 121 prominent women refuted Schechter’s contentions and the “expert opinions” of Brodzinsky and Greif. On March 12, 1987, they issued a document entitled “By These Standards, We Are All Unfit Mothers.” The document quoted from each of the expert’s testimony and included the New York Times’ summary of what commentators called Dr. Schechter’s “Patty Cake” test: Dr. Schechter faulted Mrs. Whitehead for saying “Hooray!” when the baby played Patty Cake by clapping her hands together. The more appropriate response for Mrs. Whitehead, he said, was to imitate the child by clapping her hands together and saying “Patty Cake” to reinforce the child’s behavior. He also criticized Mrs. Whitehead for having four pandas of various size available for Baby M to play with. Dr. Schechter said pots, pans and spoons would have been more suitable. Signed by Andrea Dworkin, Nora Ephron, Marilyn French, Betty Friedan, Carly Simon, Susan Sontag, Gloria Steinem, Meryl Streep, Vera B. Williams, and others, the document concluded with the statement that “we strongly urge . . . legislators and jurists . . . to recognize that a mother need not be perfect to ‘deserve’ her child.” When Cassidy made the closing argument on behalf of Whitehead, he re-emphasized that Elizabeth Stern was not, as Whitehead had been told, infertile. He also stressed that termination of parental rights was permitted by law only in the event “of actual abandonment or abuse of the child.” Finally, he warned that a ruling in favor of the contract’s enforcement would lead to “one class of Americans . . . exploit[ing] another class. And it will always be the wife of the sanitation worker who must bear the children of the pediatrician.” Sorkow announced his verdict on March 31, 1987: “The parental rights of the defendant, Mary Beth Whitehead, are terminated. Mr. Stern is formally judged the father of Melissa Stern.” Elizabeth Stern was then escorted into Sorkow’s chambers, where she adopted Baby M. New Jersey Supreme Court’s Opinion The Supreme Court of New Jersey overturned the lower court’s ruling on February 2, 1988. It invalidated the surrogacy contract, annulled Elizabeth Stern’s adoption of Baby M, and restored the parental rights of Whitehead. Writing for a unanimous court, Chief Justice Robert N. Wilentz said: We do not know of, and cannot conceive of, any other case where a perfectly fit mother was expected to surrender her newly born infant, perhaps forever, and was then told she was a bad mother because she did not. The justices then dealt with the issue as a difference between “the natural father and the natural mother, [both of whose claims] are entitled to equal weight.” Custody was awarded to William Stern and the trial court was instructed to set visitation for Mary Beth Whitehead. The court awarded Whitehead visitation on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.; every other weekend; and two weeks during the summer. (Holidays were also divided: the Sterns are entitled to Melissa’s company on her birthday, Christmas Day, and Mother’s Day, among other occasions.) Since Melissa is now in school during the week, and the Sterns live in New Jersey and Whitehead on Long Island, Whitehead reports that these circumstances have made it increasingly difficult for her to comply with the court-imposed schedule for visits with her daughter. In a recent interview, she said she would seek either a revision of the agreement’s terms or to move the rest of her family closer to Melissa’s other home in New Jersey. The New Jersey Supreme Court decision prohibited additional surrogacy arrangements in that state unless “the surrogate mother volunteers, without any payment, to act as a surrogate and is given the right to change her mind and to assert her parental rights.” Seventeen other states have since adopted similar guidelines. This case elicited a divided response from feminists. Some asserted the primacy of a mother’s claim to her child; others argued that any nullification of the contract would constitute a restriction upon a woman’s right to control her own body. For Further Reading Brennan, Shawn, ed. Women’s Information Directory. Detroit: Gale Research, 1993. Chesler, Phyllis. Sacred Bond: The Legacy of Baby M. New York: Times Books, 1988. Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn. Encyclopedia of Women’s History in America. New York: Facts on File, 1996. Davis, Flora. Moving the Mountain: The Women’s Movement in America Since 1960. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991. Evans, Sara M. Born for Liberty: A History of Women in America. New York: The Free Press, 1989. Knappman, Edward, ed. Great American Trials. Detroit: Gale Research, 1994. Sack, Kevin. “New York is Urged to Outlaw Surrogate Parenting for Pay.” New York Times, May 15, 1992. Squire, Susan. “Whatever Happened to Baby M?” Redbook, January 1994. Whitehead, Mary Beth, with Loretta Schwartz-Nobel. A Mother’s Story: The Truth About the Baby M Case. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989. Source: Women’s Rights on Trial, 1st Ed., Gale, 1997, p.312.

|

Historia kobiet

czyli

technologia reprodukcji

http://www.gale.cengage.com/free_resources/whm/trials/babym.htm

W sprawie dziecka M: 1988

Powodowie: William i Elizabeth Stern

Strona pozwana: Mary Beth Whitehead

Główni prawnicy pozwanego: Harold Cassidy i Randy Wolf

Główni prawnicy dla powodów: Frank Donahue i Gary Skoloff

Roszczenie powodów: Mary Beth Whitehead powinna wydać dziecko, które poczęła w wyniku sztucznego zapłodnienia nasieniem Williama Sterna, zgodnie z warunkami „Umowy o rodzicielstwie zastępczym” zawartej między Whitehead i Stern przed poczęciem dziecka

Sędziowie: Robert Clifford, Marie L. Garibaldi, Alan B. Handler, Daniel O'Horn, Stewart G. Pollock, Gary S. Stein i Chief Justice Robert N. Wilentz

Miejsce: Trenton, New Jersey

Data decyzji: 3 lutego 1988 r

Werdykt: prawa rodzicielskie Mary Beth Whitehead zostały zakończone, a Elizabeth Stern otrzymała prawo do natychmiastowej adopcji córki Williama Sterna i Whiteheada. Sąd Najwyższy New Jersey częściowo unieważnił ten wyrok 2 lutego 1988 r., Przywracając prawa rodzicielskie Whitehead i unieważnił adopcję Elizabeth Stern, ale przyznał opiekę nad dzieckiem Williamowi Sternowi.

Znaczenie: była to pierwsza szeroko obserwowana próba zmagania się z kwestiami etycznymi związanymi z „technologią reprodukcji”.

Koncepcja Melissy Stern miała miejsce na mocy porozumienia podpisanego w Noel Keane's Infertility Center w Nowym Jorku 5 lutego 1985 roku. Były trzy strony porozumienia: Richard Whitehead wyraził zgodę na „cele, zamiary i postanowienia” kontraktu oraz na inseminacja Mary Beth Whitehead, jego żony, nasieniem Williama Sterna. Ponadto, ponieważ każde dziecko urodzone przez Mary Beth Whitehead byłoby prawnie dzieckiem jej męża, zgodził się, że „zrzeknie się natychmiastowej opieki nad dzieckiem” i „wygaśnie jego prawa rodzicielskie”.

Mary Beth Whitehead zgodziła się być sztuczną inseminacją i nie tworzyć „relacji rodzic-dziecko” z dzieckiem. Zgodziła się, że po urodzeniu dziecka zrzeknie się praw rodzicielskich na rzecz Williama Sterna; i przyznała, że w okresie ciąży zrzeknie się prawa do podjęcia decyzji o aborcji. Mogła zabiegać o aborcję tylko wtedy, gdy płód był „fizjologicznie nieprawidłowy” lub jeśli lekarz prowadzący inseminację zgodził się, że aborcja jest wymagana, aby zapewnić jej „zdrowie fizyczne”. Whitehead zgodziła się następnie, że William Stern ma prawo wymagać wykonania amniopunkcji i że „poroni płód na żądanie Williama Sterna, jeśli zostanie zdiagnozowana wrodzona lub genetyczna nieprawidłowość”. Pomimo ograniczenia prawa Whiteheada do aborcji, umowa powierzona Sternowi odpowiedzialnemu za dziecko w przypadku, gdy Whitehead odmówi wypełnienia tej części swojej umowy: „Jeśli Mary Beth Whitehead odmówi aborcji płodu na żądanie Williama Sterna, jego zobowiązania określone w niniejszej Umowie natychmiast wygasną, z wyjątkiem obowiązków ojcostwa określonych w ustawie. ” Wreszcie Whiteheads „zgadzają się [d] przyjąć wszelkie ryzyko, łącznie z ryzykiem śmierci, które jest związane z poczęciem, ciążą i porodem”.

Stern zgodził się zapłacić Whiteheadowi 10 000 dolarów. Chociaż kwota 10 000 USD została opisana jako „rekompensata za usługi i wydatki”, a umowa wyraźnie stwierdza, że opłata „w żaden sposób nie powinna być interpretowana jako opłata za zerwanie praw rodzicielskich lub płatność w zamian za zgodę na wydanie dziecka do adopcji” , ”Była płatna tylko przy oddaniu żywego niemowlęcia. Jeśli Whitehead poroniłaby przed piątym miesiącem ciąży, nie otrzymałaby żadnego odszkodowania; jeśli „dziecko poroniło, umarło lub urodziło się martwe po czwartym miesiącu ciąży i wspomniane dziecko nie przeżyje”, Stern zgodził się zapłacić Whiteheadowi 1000 dolarów. Zapłacił także 10 000 dolarów Noelowi Keane'owi za jego usługi w przygotowaniu umowy o macierzyństwo zastępcze.

Żona Sterna, Elżbieta, nie była stroną umowy, ani nie wymieniono jej z nazwiska. Umowa określała ją tylko jako żonę Sterna. Pierwszym takim odniesieniem jest stwierdzenie, że „jedyny cel umowy”. . . ma na celu umożliwienie Williamowi Sternowi i jego niepłodnej żonie posiadania dziecka, które jest biologicznie spokrewnione z Williamem Sternem. ”„ Inne odniesienie brzmi: „W przypadku śmierci Williama Sterna, przed lub po narodzinach wspomnianego dziecka, niniejszym rozumie i zgadza się Mary Beth Whitehead, Surrogate i jej mąż Richard Whitehead, że dziecko zostanie umieszczone pod opieką żony Williama Sterna ”.

Wydarzenia nie przebiegały zgodnie ze scenariuszem umownym. 27 marca 1986 roku Whitehead urodziła córkę. Nazwała niemowlę „Sara Elizabeth Whitehead”, zabrała ją do domu i odrzuciła 10 000 dolarów. W Niedzielę Wielkanocną 30 marca Sternowie zabrali niemowlę do domu. Dziecko było z powrotem w domu Whitehead 31 marca; w drugim tygodniu kwietnia Whitehead powiedziała Sternom, że nigdy nie będzie w stanie oddać swojej córki. Sternowie odpowiedzieli, zatrudniając adwokata Gary'ego Skoloffa do walki o wyegzekwowanie umowy. Przybyła policja, aby usunąć „Melissę Elizabeth Stern” z aresztu Whitehead; pokazali akt urodzenia „Sary Elizabeth Whitehead”, wyszli. Kiedy policja wróciła, Whitehead przekazała córkę przez otwarte okno mężowi i błagała go, aby uciekł.

Rozpoczyna się proces

Proces rozpoczął się 5 stycznia 1987 r., Kiedy to wyznaczono przedstawiciela dziecka, znanego jako „Baby M”, czyli Melissa. Sternowie otrzymali tymczasową opiekę. Whitehead, któremu sędzia Harvey Sorkow polecił zaprzestać karmienia dziecka piersią, miał tymczasowo przydzielane dwie godzinne wizyty w tygodniu, „ściśle nadzorowane pod stałym nadzorem. . . w odosobnionym, nadzorowanym miejscu, aby zapobiec ucieczce lub obrażeniom ”.

Skoloff sformułował „kwestię do rozstrzygnięcia” jako „czy obietnica złożenia daru życia powinna być egzekwowana”. Stwierdził, że „Mary Beth Whitehead zgodziła się dać Billowi Sternowi dziecko z jego własnego ciała i krwi” i podkreślił, że stwardnienie rozsiane Elizabeth Stern „uczyniło ją z praktycznego punktu widzenia bezpłodną. . . ponieważ nie mogła nosić dziecka bez poważnego zagrożenia dla jej zdrowia ”.

Harold Cassidy, adwokat Whitehead, przedstawił alternatywny pogląd we własnych uwagach wstępnych: „Jedynym powodem, dla którego Sternowie nie próbowali począć dziecka, był. . . ponieważ pani Stern miała karierę, która musiała być zaawansowana. . . . To, co ma pani Stern, to [stwardnienie rozsiane] rozpoznane jako najłagodniejsza postać. Nigdy nie została nawet zdiagnozowana, dopóki nie obaliliśmy jej w tej sprawie. . . . Jesteśmy tutaj ”- podsumowała Cassidy -„ nie dlatego, że Betsy Stern jest bezpłodna, ale dlatego, że jedna kobieta wstała i powiedziała, że są rzeczy, których nie można kupić za pieniądze ”. Neurolog związany z Mount Sinai School of Medicine zeznał, że Elizabeth Stern cierpiała na „bardzo, bardzo, bardzo niewielki przypadek SM, jeśli w ogóle”.

Kiedy poruszono kwestię opieki, Skoloff stwierdził, że prawo umów i dobro niemowlęcia nakazują przyznanie wyłącznej opieki Sterns: „Jeśli jest jeden przypadek w Stanach Zjednoczonych, gdzie wspólna opieka nie będzie działać, gdzie wizyta prawa nie zadziałają, tam gdzie zachowanie praw rodzicielskich nie zadziała, to jest to. ” Zwrócił się bezpośrednio do Sorkowa: „Wysoki Sądzie, zarówno zgodnie z teorią kontraktu, jak i teorią interesu, musisz wyrzec prawa Mary Beth Whitehead i pozwolić Billowi Sternowi i Betsy Stern być matką i ojcem Melissy”.

Przedstawicielka Baby M., Lorraine Abraham, zajęła stanowisko, aby przedstawić własną rekomendację. Powiedziała sądowi, że formułując własny wniosek częściowo oparła się na opiniach trzech biegłych: psychologa dr Davida Brodzińskiego; pracownik socjalny dr Judith Brown Greif; i psychiatra dr Marshall Schechter. Abraham stwierdził, że eksperci „będą. . . zalecić temu sądowi przyznanie opieki Sternom i odmowę odwiedzin w tym czasie ”. Abraham, która musiała przedstawić własną opinię jako przedstawicielka Baby M, dodała, że „zmusiła ją przytłaczająca waga dochodzenia [trzech ekspertów], aby przyłączyła się do ich rekomendacji”.

Podczas zeznań Elizabeth Stern, Randy Wolf, jeden z prawników Whitehead, zapytał ją: „Czy martwiłeś się, jaki wpływ na dziecko będzie miało odebranie dziecka Mary Beth Whitehead?”

Stern odpowiedział: „Wiedziałem, że będzie to trudne dla Mary Beth i w najlepszym interesie Melissy”.

Wolf powiedział wtedy: „Teraz sądzę, że zeznałeś, że jeśli Mary Beth Whitehead otrzyma opiekę nad dzieckiem, nie chcesz go odwiedzać”.

Stern odpowiedział: „Zgadza się. Nie chcę odwiedzać ”.

Następnie Skoloff podniósł pytania dotyczące kondycji Whitehead jako matki. Whitehead ukrył się na Florydzie z Baby M wkrótce po narodzinach niemowlęcia, a Skoloff przedstawił to jako dowód niestabilności. Następnie zagrał dla sądu nagraną rozmowę telefoniczną między Mary Beth Whitehead i Williamem Sternem:

Stern: Chcę z powrotem moją córkę.

Whitehead: I ja też jej chcę, więc co robimy, przeciąć ją na pół?

Stern: Nie, nie, nie przecinamy jej na pół.

Whitehead: Chcesz mnie, chcesz, żebym zabił siebie i dziecko?

Stern: Nie, właśnie dlatego ci ją oddałem, bo nie chciałem, żebyś się zabił.

Whitehead: Karmię ją piersią od czterech miesięcy. Jest ze mną związana, Bill. Śpię z nią w tym samym łóżku. Ona nawet nie będzie spać sama. Co zrobisz, gdy zdobędziesz tego dzieciaka, który wrzeszczy i kontynuuje swoją matkę?

Stern: Będę jej ojcem. Będę dla niej ojcem. Jestem jej ojcem.

Stern: Podpisałeś umowę. Podpisałeś umowę.

Whitehead: Zapomnij o tym, Bill. Powiem ci teraz, wolałbym raczej zobaczyć mnie i ją martwą, zanim ją zdobędziesz.

Następnego dnia zeznawała Mary Beth Whitehead. Jeden z jej prawników zapytał: „Jeśli nie uzyskasz prawa do opieki nad Sarą, czy chcesz ją zobaczyć?”

Whitehead odpowiedział:

Tak, jestem jej matką i czy ten sąd pozwala mi widzieć ją tylko przez dwie minuty w tygodniu, dwie godziny w tygodniu, czy przez dwa dni, jestem jej matką i chcę ją widzieć bez względu na wszystko.

Następnie zeznania biegłego. Dr Lee Salk, wpływowy psycholog dziecięcy, zeznawał za Sternami. Whitehead, określany już w dokumentach sądowych „ciążą strony trzeciej”, będzie teraz nazywany „zastępczą macicą”. „Użyty termin prawny to„ wygaśnięcie praw rodzicielskich ”- zaczął Salk,

i nie widzę, żeby istniały jakieś „prawa rodzicielskie”, które istniały w ogóle. . . . Umowa obejmowała dostarczenie komórki jajowej przez panią Whitehead do sztucznego zapłodnienia w zamian za 10 000 dolarów. . . dlatego mam poczucie, że zarówno pod względem strukturalnym, jak i funkcjonalnym, rolę państwa Stern jako rodziców spełnia zastępcza macica, a nie zastępcza matka.

Dr Marshall Schechter zeznał, zgodnie z przepowiednią Abrahama, że jego zdaniem prawo do opieki nad Sternami powinno zostać przyznane. Oświadczył, że Whitehead cierpi na „zaburzenie osobowości z pogranicza” i że „wydanie dziecka Panu Whiteheadowi przez okno jest nieprzewidywalnym, impulsywnym aktem, który należy do tej kategorii”. Następnie, powołując się (między innymi) na to, że Whitehead ufarbowała włosy, aby ukryć ich przedwczesną biel, dodał diagnozę „narcystycznego zaburzenia osobowości”.

Pracownik socjalny psychiatryczny z Bostonu, dr Phyllis Silverman, zaprzeczył opisywaniu przez Schechtera zachowania Whiteheada jako „szalonego”:

Reakcja pani Whitehead jest podobna do reakcji innych „urodzonych matek”, które odczuwają ból, żal i wściekłość nawet przez 30 lat po oddaniu dziecka. Więź matki karmiącej z dzieckiem jest bardzo silna.

„Zgodnie z tymi normami wszyscy jesteśmy niezdolnymi matkami”

Poza salą sądową 121 wybitnych kobiet odrzuciło argumenty Schechtera i „opinie ekspertów” Brodzińskiego i Greifa. 12 marca 1987 r. Wydali dokument zatytułowany „Zgodnie z tymi standardami wszyscy jesteśmy niezdolnymi matkami”. Dokument cytowany z zeznań każdego eksperta i zawierał podsumowanie New York Timesa na temat tego, co komentatorzy nazwali testem „Patty Cake” dr Schechtera:

Dr Schechter zarzucił pani Whitehead, że powiedziała „Hurra!” kiedy dziecko bawiło się Patty Cake, klaszcząc w dłonie. Powiedział, że bardziej odpowiednią reakcją dla pani Whitehead jest naśladowanie dziecka poprzez klaskanie w dłonie i mówienie „Patty Cake”, aby wzmocnić zachowanie dziecka. Skrytykował także panią Whitehead za posiadanie czterech pand różnej wielkości dla Baby M. Dr Schechter powiedział, że garnki, patelnie i łyżki byłyby bardziej odpowiednie.

Podpisany przez Andreę Dworkin, Norę Ephron, Marilyn French, Betty Friedan, Carly Simon, Susan Sontag, Glorię Steinem, Meryl Streep, Verę B. Williams i innych, dokument kończy się stwierdzeniem, że „gorąco namawiamy. . . ustawodawcy i prawnicy. . . uznać, że matka nie musi być idealna, aby „zasłużyć” na swoje dziecko ”.

Kiedy Cassidy wygłosił końcowy argument w imieniu Whiteheada, ponownie podkreślił, że Elizabeth Stern nie była, jak powiedziano Whiteheadowi, bezpłodna. Podkreślił również, że wygaśnięcie praw rodzicielskich jest dozwolone przez prawo tylko w przypadku „faktycznego porzucenia lub znęcania się nad dzieckiem”. Na koniec ostrzegł, że orzeczenie na korzyść wykonania kontraktu doprowadzi do „jednej klasy Amerykanów. . . wykorzystać [ing] inną klasę. I zawsze to żona pracownika sanitarnego będzie musiała rodzić dzieci pediatry ”.

Sorkow ogłosił swój werdykt 31 marca 1987 roku: „Prawa rodzicielskie pozwanej Mary Beth Whitehead wygasły. Pan Stern jest formalnie uznany za ojca Melissy Stern ”. Elizabeth Stern została następnie eskortowana do komnat Sorkowa, gdzie adoptowała Baby M.

Opinia Sądu Najwyższego New Jersey

Sąd Najwyższy stanu New Jersey 2 lutego 1988 r. Uchylił orzeczenie sądu niższej instancji. Unieważnił on umowę o macierzyństwo zastępcze, unieważnił adopcję Baby M przez Elizabeth Stern i przywrócił prawa rodzicielskie Whitehead. Pisząc do jednogłośnego sądu, prezes Robert N. Wilentz powiedział:

Nie znamy i nie możemy sobie wyobrazić żadnego innego przypadku, w którym oczekiwano, że doskonale sprawna matka odda swoje nowo narodzone dziecko, być może na zawsze, a następnie powiedziano jej, że jest złą matką, ponieważ tego nie zrobiła.

Następnie sędziowie potraktowali tę kwestię jako różnicę między „naturalnym ojcem a naturalną matką, [której oba roszczenia] mają jednakową wagę”. Opiekę nad dzieckiem przyznano Williamowi Sternowi, a sądowi polecono wyznaczenie wizytacji Mary Beth Whitehead.

Sąd zezwolił na odwiedziny Whitehead we wtorki i czwartki od 10:30 do 16:30; co drugi tydzień; i dwa tygodnie latem. (Święta również były podzielone: Sternowie mają prawo do towarzystwa Melissy m.in. w jej urodziny, Boże Narodzenie i Dzień Matki). Ponieważ Melissa jest teraz w szkole w ciągu tygodnia, a Sternowie mieszkają w New Jersey i Whitehead na Long Island, Whitehead informuje, że okoliczności te utrudniają jej przestrzeganie nałożonego przez sąd harmonogramu wizyt z córką. W niedawnym wywiadzie powiedziała, że będzie dążyć albo do zmiany warunków umowy, albo do przeniesienia reszty rodziny bliżej innego domu Melissy w New Jersey.

Decyzja Sądu Najwyższego New Jersey zakazała dodatkowych ustaleń dotyczących macierzyństwa zastępczego w tym stanie, chyba że „zastępcza matka zgłosi się na ochotnika, bez żadnych opłat, do pełnienia funkcji zastępcy i ma prawo zmienić zdanie i dochodzić swoich praw rodzicielskich”. Od tamtego czasu siedemnaście innych stanów przyjęło podobne wytyczne.

Ta sprawa wywołała podzieloną reakcję feministek. Niektórzy twierdzili, że matka ma pierwszeństwo wobec swojego dziecka; inni argumentowali, że zniesienie umowy stanowiłoby ograniczenie prawa kobiety do kontrolowania własnego ciała.

Do dalszego czytania

Brennan, Shawn, wyd. Katalog informacji dla kobiet. Detroit: Gale Research, 1993.

Chesler, Phyllis. Sacred Bond: The Legacy of Baby M., New York: Times Books, 1988.

Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn. Encyklopedia historii kobiet w Ameryce. New York: Facts on File, 1996.

Davis, Flora. Moving the Mountain: Ruch kobiet w Ameryce od 1960 roku. Nowy Jork: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

Evans, Sara M. Born for Liberty: A History of Women in America. New York: The Free Press, 1989.

Knappman, Edward, wyd. Wspaniałe amerykańskie próby. Detroit: Gale Research, 1994.

Worek, Kevin. „Nowy Jork jest wezwany do wyjęcia spod prawa rodzicielstwa zastępczego za wynagrodzenie”. New York Times, 15 maja 1992.

Squire, Susan. „Co się stało z Baby M?” Redbook, styczeń 1994.

Whitehead, Mary Beth i Loretta Schwartz-Nobel. A Mother's Story: The Truth About the Baby M. Nowy Jork: St. Martin's Press, 1989.

Źródło: Women's Rights on Trial, 1st Ed., Gale, 1997, s.312.